Graphic arts: how will COVID-19 affect the industry’s future?

John Morent, owner of POP Solutions, foresees the death of deregulated capitalism and the hyper-consumerism it encourages, and asks how FESPA members can work together to forge a brave new world.

What will be the long-term impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the graphic arts industry? That is the question I have been asked today by FESPA, which brings together 16,000 members from all around the world. As simple as it may seem at first glance, this question requires us to step back and put things into perspective.

Furthermore, the intensity of the crisis and the momentum of the virus should stop us reacting with our reptilian brain, which triggers automatic responses based on past experiences, and to tackle the problem in a holistic and interdisciplinary way, even if that means reshaping our ways of thinking. The underlying questions are the following: what will the post-COVID world look like and what are the potential economic and social consequences of the pandemic?

John Morent, POP Solutions

More precisely, contemplating a pre-and post-health crisis era encourages us to reflect on the possibility for these peculiar times to bring about a change of direction towards a more sustainable development that more and more people are calling for. In the richest and most industralised countries, people are becoming aware that a change of behaviour is necessary.

These citizens harbour the hope that by doing so, we could give more meaning to our lives. Nevertheless, adopting a more eco-friendly way of life, reducing our consumption and our waste of resources and fostering the circular economy will only be possible if this new economic order is framed by regulation and guided by political ambition.

Political leaders and the route towards sustainable development

The short term

The current lockdown, as well as the various measures taken by governments, are the result of the lack of an upfront strategy to tackle a pandemic. With the exception of South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong, which were struck by the SARS epidemic in 2003, most countries had not designed any risk management plan beforehand. As a consequence, policymakers have been forced to decide upon last-minute written and structured plans to be implemented rapidly. It seems that most governments were convinced until now that such a pandemic would never happen despite the lessons that the last 100 years should have taught us.

Taking advantage of the lack of a coherent battle plan and of the subsequent independent supply of medical and sanitary equipment, the virus spread at such a rate that our governments were overwhelmed and compelled to react in haste. The forthcoming debate on the management of the crisis will focus on that single aspect, and it is by analysing the causes of our lack of preparation that we will be able to adopt a better strategy for the future. The fact that very few people had seen the crisis coming is highly unusual and we should learn from this.

Those who do not grow are doomed to disappearJudging by the statements of our political leaders, health has become a universal value that prevails above all others. Some would argue that regarding health as the supreme value is a misconception, and the pursuit of happiness should hold that position. In such a case, economic success but also the values of justice, social equity and education should be viewed as the tools that could help us reach that goal.

Absolute netarchy

We believe that social justice remains an indispensable condition for a sustainable economic system to arise. A social pact without social fairness is no longer a possibility. Yet in our countries, social justice is based on a welfare state that depends on the economic model of infinite growth. This neoliberal model, inherited from the Reagan and Thatcher era, is entering a new phase called “netarchical” capitalism, in which a few individuals concentrate a lot of power in their hands and are able to make their wealth grow without having to produce anything. The rise of the internet has enabled them to conquer entire sections of the economy. Netarchical companies such as the GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon) exemplify this phenomenon. Today, Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” still rules the economy. For supporters of the Scottish economist’s theories, the market regulates itself in such a way that the little fish are eaten by the big ones. In other words, in our current system, those who do not grow are doomed to disappear.

Before addressing the way that COVID-19 will reshape the printing industry, we need to remember that political decisions will play an essential role in this evolution. Should a change happen, it would first require a strong willingness to change as well as a long-term global, or at least a regional, action plan.

This kind of change and of fundraising already occurred in the past. We could mention Roosevelt’s New Deal in 1933, the 1951 Treaty of Paris that formed the bedrock of the EEC or, more recently, the creation of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development following the collapse of the Soviet bloc. At present, the European Green Deal presented to the European Commission by its President Ursula von der Leyen and amounting to €100 billion seems to be the solution. We can only hope that it will be reinforced and implemented earlier than foreseen.

At this stage, it is almost unimaginable that a plan of such a magnitude could be rapidly agreed by the 27 EU members. Differences of opinion are patent as was demonstrated on the occasion of an ECOFIN summit on coronabonds. The spirit of solidarity, the driving force of the European project, is lacking. In order to win victories in such battles or to write their names down in history, policymakers should collaborate, not clash. Yet on the European stage, as on the national one, confrontation logic still prevails. On the one hand, our democracies are threatened by the rise of populist movements but, on the other hand, we notice a timid interest among young people for public affairs that could make us hope for the better.

Other stakeholders

In the graphic arts industry, retailers and multinationals as well as consumers are key stakeholders. No need to say that policymakers are omnipresent in this triangle, but their role is solely regulatory. As representatives of the nation, they set the institutional and legal framework in which we live together.

As for retailers and multinationals, these two big stakeholders look very much alike. They depend on each other for their proper functioning, are listed on the stock exchange and respond to a great extent to the theories of the Chicago school of economics that assume that these incorporated companies are foreseen by the law in order to facilitate the concentration of capital and that their legal objective is to create as much profit as possible in the shortest timeframe. That school of thought differs from Modern Monetary Theory, which, instead of contemplating only the single interests of shareholders, offers a more modern approach that includes the employees, the suppliers, the bankers, the workers and so on, among the stakeholders.

Aware of deepening inequalities and realistic about the often worse situation in other countries, citizens are convinced that it is high time to change things

Changes in the short, middle and long term depend on the tendencies that take shape within the boards of directors of these listed companies. There is no one-size-fits-all model. The women and men who sit within the boards could be more or less prone to change their strategies, currently based on an increasingly short-term vision, in order to opt for a cause in the long run. If they succeed in defending their case in front of the shareholders, one could think that the companies that adopt a long-term strategy and invest more now so as to make more profit in 10 years will be in the winner’s seat. What it takes are competent and convinced leaders.

If the policymakers do not change course and do not decide on a realistic and sustainable action plan to be implemented in one generation, we cannot expect the above-mentioned stakeholders to induce this reorientation. In the absence of a global consensus on this matter, more ethical retailers and multinationals would lose competitiveness, would be pushed away from the market and would eventually disappear.

Time has come to touch upon another stakeholder, that is to say the consumer, or more broadly speaking, the citizen. That is precisely when things get more complicated, because we are all concerned. Politicians, let us not forget, are but the voice of the people. We elect these men and women and we can pass our thoughts onto them and influence our destiny in place of enduring it.

Solidarity between individualistic yet universalist citizens

The French case

For the most part, French citizens declare that we should act in order to preserve our planet. They claim it in their speeches, or during the demonstrations they organise. Yet, the fact remains that, when President Hollande tried to convince the electorate to restrain their individual freedom through the creation of a carbon tax, or when President Macron attempted to lower the speed limit from 90 km/h to 80 km/h on the main roads for the latter, they triggered the red caps and yellow jackets movements.

Aware of deepening inequalities and realistic about the often worse situation in other countries, citizens are convinced that it is high time to change things. Nevertheless, they seem to agree to such a change only for their benefit and never at their cost – a reaction well captured in the famous expression not in my backyard.

Citizens are torn between individualism and universalism. They are universalist in their assertions yet individualist in their actions. Therefore, it would be worth educating and raising people’s awareness of public affairs so as to give everyone the desire to make some efforts, to get involved, to read and to keep themselves informed not only by watching the television, the mass medium par excellence.

From a social point of view and in the absence of a change of political dynamics, the crisis will increase even more inequalities. In order to bring about some change, policymakers should strive for a pay rise for teachers and blue-collar workers as well as for a better financing of the justice system.

We have now described all the stakeholders.

What can we expect for the graphic industry in particular?

- Assuming no changes in policy, the consequences of the pandemic will be the disappearance of the weakest, among which are quality undertakings that will not be able to face the new burdens and challenges.

- An increased corporate concentration is to be feared and could happen at a low cost for the buyers.

- In the long run, we risk losing the undertakings’ know-how to the only advantage of shareholders, multinationals, retailers and, of course, big and financially strong graphic design companies. These would have no other choice but to try to always make more profit and to reduce costs which in turn will increase inequalities and undermine an already ailing social justice.

Beyond this cruel diagnosis, human innovation could bring us some hope.

Brick and mortar retail shops remain necessary, as has been demonstrated by the crisis. Human beings need social contacts. The unanimous political reactions to the current situation also show that in difficult times we are primarily driven by our emotions.

The visual communication industry aims precisely at triggering emotions through the work of its graphic designers and publicists.

Since the primary goal of the other stakeholders is to sell products to consumers and since they are eager to double down on their efforts so that the current system does not get out of breath, they will not bring about any change. For that matter, it is worth noting that the impediment to discounts due to logistical difficulties is benefiting retailers and multinationals.

No discount simply means a lowering of advertising expenses. Therefore, the crisis is generating many profits for them whereas consumers are paying the price now that their usual shopping basket now costs 25% more. After the crisis, it will be business as usual for retailers and multinationals. However, it would be wrong to point the finger at them. If they spend money on communication and discounts, it is foremost in order to sell their products and it is only natural that they should try to adapt to a new situation they did nothing to create.

Despite the usefulness of point of purchase, it is a fact that online purchases are booming. E-commerce is the big winner of this crisis – not only because its market share has gone up 46% in France in two months but also because new consumers have been encouraged to buy online for the first time. In other words, the pandemic is worth billions of euros in advertising terms. In this context, I am afraid the hypermarkets will lose market shares as they belong to a distribution mode that struggles to organise itself – with some exceptions, of course.

Policymakers could choose to educate consumers massively so that they can become “prosumers”

And now what about the citizen and consumer reaction? Does he/she really want some change? Absolutely! Is he/she ready to make the necessary sacrifices? Absolutely not, and that is where the shoe pinches. As a matter of fact, the climate crisis will be more lethal than the pandemic in the long run. However, the current media hype around the virus could offer a solution. Holistic information about the consequences and stakes of the pandemic, unbiased debates and common sense could lead to a change in consumption patterns. For instance, is it really sensible – no offence to some economists – to import kiwi fruit in winter from the other side of the globe in spite of the inherent ecological cost? Currently, money is the only exchange currency and it is about time to create an ecological currency, not in the form of new taxes but in the form of a carbon footprint that would be quantified for each product and above all explained to the consumer.

We live in an era of consumerism. At school or at university, there is almost no teaching on consumption challenges as regards rights and obligations or the environmental issues. Education in this field barely exists. Policymakers could choose to educate consumers massively so that they can become “prosumers”.

Conclusion

For the printing industries in particular, I deem it necessary to diversify the kinds of services we offer and to enter the e-commerce world if it has not already been undertaken. I am of the opinion that a local implementation is vital so as to avoid useless movements that do nothing but worsen the climate crisis. The relocation of industries makes sense and it is not a question of protectionism but of common sense.

The simple mention of the smallest barrier to trade is enough to make some economists fear a tragedy. I can understand their arguments, but I still believe that they are forgetting that decisions can be implemented step by step and at a slow pace so as to avoid waves of panic and a global recession.

Regarding the FESPA members, it seems to me that co-creation among members of a global association could bring about a multiplied added value. In the framework of sustainable development, replacing competition by mutual assistance could help businesses evolve rapidly, even if they have not reflected yet on what could be done and for what price.

I am equally convinced that today it is in my customers’ real interest to engage in that path. Consequently, I would be happy to debate that issue with FESPA members so that tomorrow we could be stronger together. FESPA is the appropriate setting to commit together on an issue that will be placed at the centre of its work in this decade, or so I hope.

If we want change to happen, we have to influence our policymakers so that they choose guidelines and design a plan and subsequently implement it thoroughly. It is our responsibility as managers.

What I fear most is that after the COVID crisis we go back to business as usual

We could contemplate creating a European fund for climate transition and sustainable development financed by the member states and a tax on multinationals working on European ground. The advantage of such a system would be to get rid of fiscal dumping between European countries and to influence the global economy thanks to a model that could hardly ever be invented by the Trump administration or the Beijing authorities. This is a possible option, but it would require the 27 member states to agree on a common solution not for an acute crisis such as COVID but on a common ambition for Europe and subsequently for the world as a whole. If we also manage to put the social fairness issue at the centre of the debate, we could offer a better world to the next generations.

What I fear most is that after the COVID crisis we go back to business as usual. That would lead to the disappearance of the less financially strong undertakings, to the loss of know-how in the long run and to the increase of social inequalities. Yet I am strongly convinced that business managers have also a social responsibility beside the policymakers.

I still harbour the secret hope that a burst of civic spirit, a matured reflection on co-creation on the political level and, above all, innovation and common sense will eventually prevail. Yes, but when?

Become a FESPA member to continue reading

To read more and access exclusive content on the Club FESPA portal, please contact your Local Association. If you are not a current member, please enquire here. If there is no FESPA Association in your country, you can join FESPA Direct. Once you become a FESPA member, you can gain access to the Club FESPA Portal.

Topics

Recent news

Sustainability, seaweed and storytelling

Joanne O’Rourke, winner of the Epson Design Award, discusses the interface between storytelling, nature, craft and innovation in her business, and how the Personalisation Experience 2025 was a career-defining moment.

What’s new in stamping foils? Bringing extra sparkle to print products

Stamping foil can help your products to really stand out – and you can probably do it with the equipment you already have. We speak to Matt Hornby of foil specialists Foilco.

The intelligence behind the ink: how AI is changing printing forever

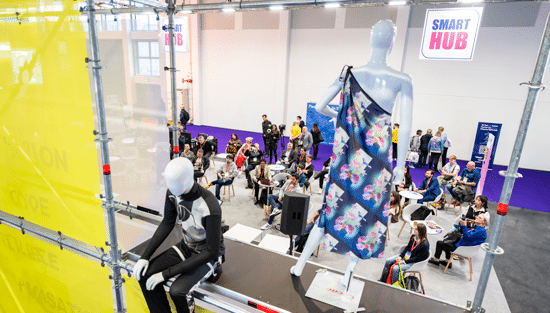

Keypoint Intelligence, the global market data leader for the digital imaging industry, showed the growing application of artificial intelligence to all facets of printing at the SmartHub Conference at the Personalisation Experience 2025, co-located at the FESPA Global Print Expo earlier this month.