Industrial printing is a broad term for decorating products or integrating printing into manufacturing. It includes direct-to-object personalisation and functional applications like printing on tiles or packaging. This market is expanding with technologies like inkjet, which allows for on-demand production and customization.

Many wide format printer vendors look to industrial printing as a potential new market but there’s no real definition of what industrial printing means, which in turn makes it harder for print service providers to see where exactly those opportunities might lie. This is because the phrase ‘industrial printing’ is more of an umbrella term that covers several different market areas. In some cases, it’s just a matter of marketing existing print services to new customers, but others require changes in print technology, typically new ink formulations, while yet others are more about integrating printing into other manufacturing processes.

Even the word ‘industrial’ has various meanings to different people. For some, industrial is the exact opposite of pretty, conjuring up images of chimneys spewing waste into the atmosphere. In printing, it’s used to signify something more functional than graphic art output. But in some contexts, industrial means robust or hard working. In general, we expect industrial products to last longer, with fewer breakdowns and lower maintenance requirements. This is likely to filter into the graphic arts market as more wide format equipment is used in industrial settings.

Some definitions of industrial printing suggest that it should apply to anything other than printing to paper, which would mean anything other than general commercial work, as well as books, magazines or newspaper printing. But since paper is rarely used in most wide format printing, this definition is just too narrow.

Instead, there are broadly two different ways that we can think of industrial printing. The first is essentially as a way of decorating products. That is, taking products that have already been manufactured and then adding an extra printed element to them at a later stage. There are several Direct-to-Shape printers designed to print to cylindrical objects, such as glasses, bottles or even candle holders. Inkcups, for example, sells the Helix range which all take objects up to 305mm in length but with a 218mm print area. Amica makes the 3Sixty range, which will handle bottles with a diameter of 40mm to 120mm, and length of 110 to 270mm though the maximum print length is 220mm.

These DtS printers are matched by a growing number of small flatbed printers that can print to small objects such as smartphone cases or pencil boxes but equally be used to add graphics to small machine parts. Mimaki, Mutoh and Roland DG have all developed a number of printers ranging from A3 up to A1 sizes to help print service providers expand into the promotional and industrial markets. Epson makes an even more compact device, the SureColor V1000, which is designed to sit on a counter in a retail environment for on-demand personalisation. It has an A4-sized platen and can print to small items such as fridge magnets. Azon sells the Matrix Monster Jet, which can print to objects up to 1m in height and is used for decorating items such as suitcases and even washing machines.

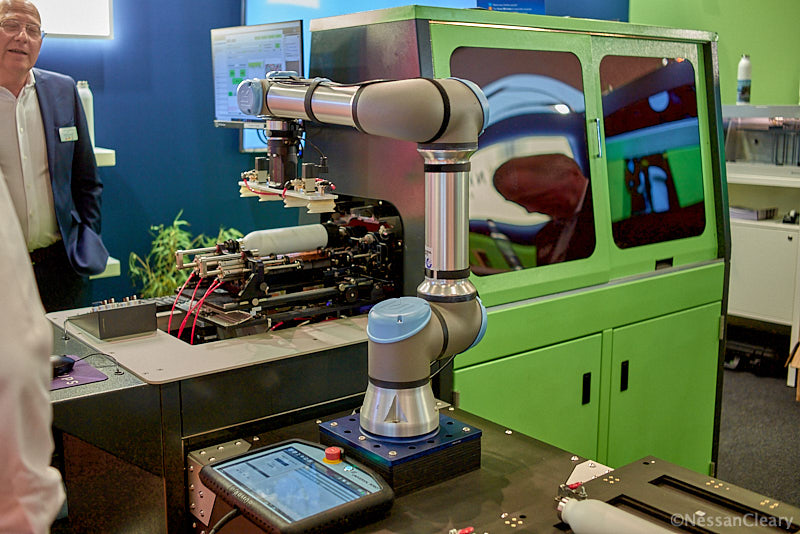

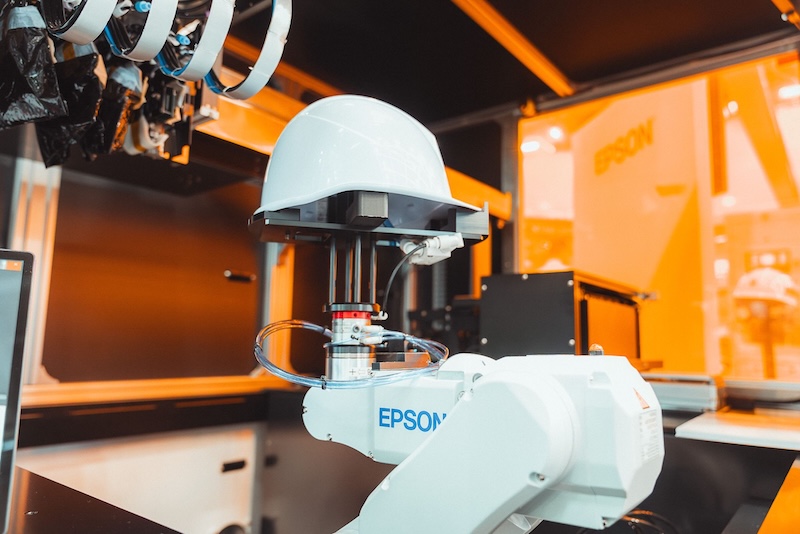

For now, all these printers mainly print to flat objects, or those with very slight curves though some can also be fitted with an optional jig to rotate cylindrical items. But as this market grows we are likely to see more direct-to-object printers appearing that are able to handle complex shapes. Epson, for example, recently revealed that it is developing a DtS printer that uses a six axis robotic arm to rotate small items to present different aspects of them to the printheads.

All of these printers use UV inks combined with LED curing. The standard inksets start with cyan, magenta, yellow and black but usually also include white and varnish. Some also have an extra channel for a primer, which can extend the range of surfaces they can print to.

However, there is also a cheaper, more flexible option in the form of UV DtF printers. These print the graphic to a transfer film so that the print can be applied to the object at a later stage. Most use CMYK but RS Pro demonstrated a useful model at this summer’s Fespa Global show which included an extra roller for foil effects such as gold or silver.

The second type of industrial printing is where the printing is part of a manufacturing process, needed to complete the product. That could mean printing instructions for use onto a product, or a barcode for track and trace uses. Some of this type of printing used to involve labels, but improvements in inks has allowed this information to now be printed directly to products, eliminating the labelling step and its associated waste.

Printing is also used for more functional purposes, such as printed electronics or producing membrane switches, or even for printing flooring and counter tops, where there is enough short run on-demand work to justify the use of inkjet. Then there is ceramic tile production, which is almost entirely printed digitally because the non-contact nature of inkjet helps to avoid costly breakages. Indeed, the push to digitise the ceramic tile market led directly to the development of recirculation channels in modern printheads, which has made it easier to jet more functional inks, both for graphics and industrial printing.

Packaging printing can also be classed as industrial print, especially as it’s becoming more common for manufacturers to take their packaging in-house. Some packaging is purely functional, such as coding and marking, which may also include health warnings as well as information on recycling the product and the packaging. But there is also a lot of graphics on packaging, which forms part of the product marketing, and can include everything from boxes to tins, bottles and lids.

Some textile printing can also be classed as industrial print, particularly in the home decor market. Products such as curtains, duvet covers, and fabrics for chairs and sofas will all be printed as part of their original manufacturing. Today much of this is done with rotary screen printers but there is a growing number of roll to roll textile printers, including a number of single pass inkjet textile presses.

The expectation is that most industrial printing going forward will be via inkjet, which is probably true. Digital has certainly allowed short run promotions and personalisation. Digital also allows manufacturers to take advantage of improvements in e-commerce ordering to produce items locally and on-demand. But it’s worth remembering that offset litho and flexography, and even some rotogravure are also used for some industrial print applications, particularly where longer manufacturing runs are involved. And, of course, screen printing is still widely used in the industrial market, because of the range of inks available for different substrates, as well as its overall speed and relatively low cost. Regardless of the print technology, the industrial print market is only just beginning to open up as manufacturers and consumers become aware of the possibilities.