Simon Eccles provides a three part practical guide to file formats for print. Here is part two.

This is the second part of the FESPA guide to print file formats. Please also refer to part 1 where you can find the full list of filenames with URLs and part 3.

Encapsulated PostScript (.EPS)

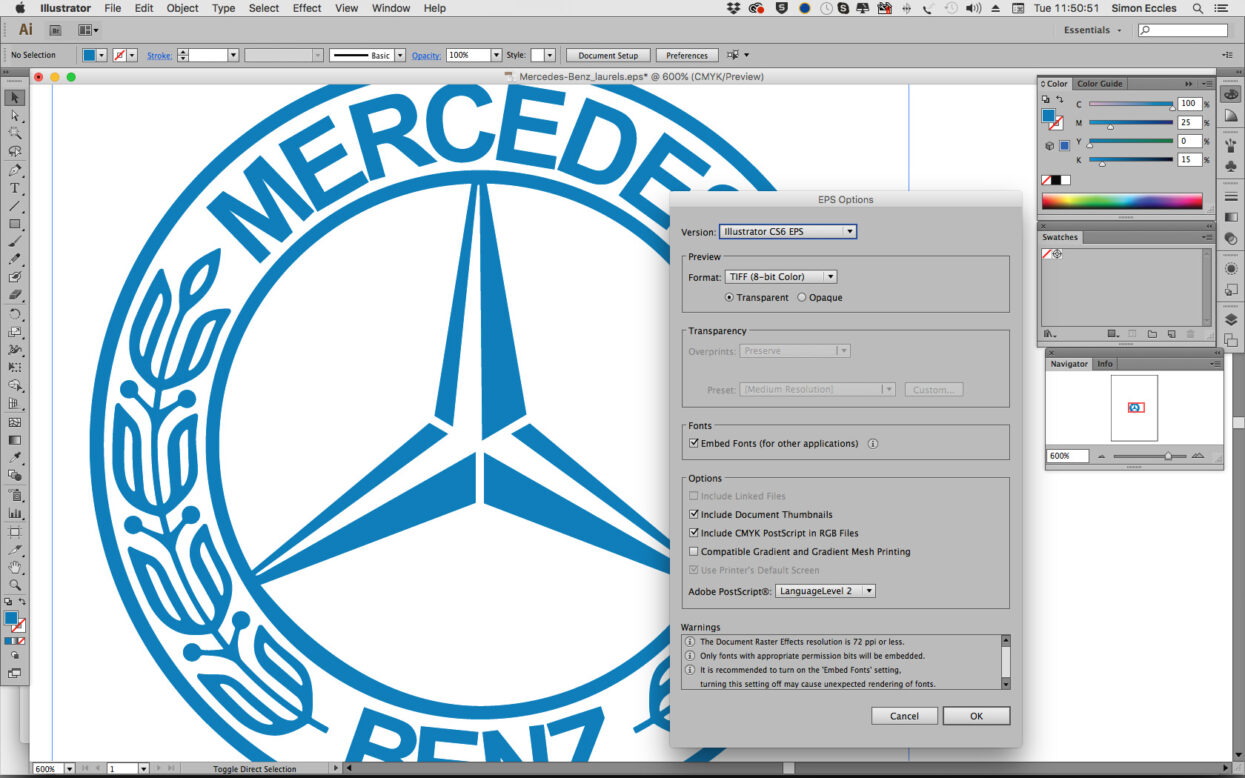

A once-important format that is becoming rarer in use, although Illustrator and Photoshop will still write it. It was essentially a predecessor to PDF, that contained text, vector and raster elements in a container that could be placed as a picture in layout programs such as QuarkXPress or InDesign.

The current Adobe Illustrator AI format has largely replaced the need for EPS, as today’s AI is in effect a PDF that preserves editable Illustrator features. Illustrator still gives the option to preserve editability in the EPS it writes.

EPS is a file “wrapper” for PostScript elements that also includes a low-resolution preview that shows the image on-screen in the layout file, but still exports full resolution raster elements or resolution-independent vector elements when you print the layout file (or export it to PDF, which is more common nowadays).

Caption: EPS can be generated by Illustrator and several other design programs.

EXIF (no extension)

A standardised image metadata format used by digital cameras and some scanners. It records camera settings, date, time, GPS data and the like. It never appears as a file in its own right, hence the lack of filename extension. It can be embedded in TIFF, JPEG or WAV (audio) files.

An unfortunate aspect of EXIF is it records a nominal resolution for the camera, invariably 72 dpi, which may affect the initial import size into a layout program. This only serves to confuse some designers who don’t understand that the total pixel count is all that matters for print quality, not the nominal dots-per-inch.

Graphics Interchange Format (.GIF)

Usually called GIF. Originally a pre-Internet, pre-Photoshop image format to create very small file sizes in the days of modems and limited bandwidths.

GIF is limited to 256 colours, which users can choose themselves from the RGB 24-bit palette (16.7 million colours). Photoshop and some other programs support it, including palette choice.

Consequently it’s not brilliant for photographs but works well for logos, especially on web pages. Unlike TIFF, it can easily be displayed on any web page. JPEG, which can also display easily in web pages, blurs edges on very small graphics.

GIF images use lossless compression so edges are sharp. It also allows a transparent background, so logos can be displayed as cutouts in web pages, unlike JPEGs. Note that PNGs can also have transparent backgrounds.

Today there’s little point in using GIF deliberately in print, but it remains popular as a format for looped animations for websites and mobile phones.

Caption: Banner ads are typical applications for static GIFs.

HDR

Standard for High Dynamic Range. It’s a variation of TIFF used as an export format by several apps that can create HDR images with very wide tonal ranges in shadows and highlights, usually by blending three or more photographs with different exposures. It must be converted to another format for print and some of the tonal range will probably be lost.

JPEG (JPG or JPEG)

A very widely used compressed file format used for bitmap graphics, such as photographs. Any image bitmap editing program can open, edit and re-save JPEGs. Digital cameras commonly export JPEGs.

JPEG stands for “Joint Photographic Experts Group,” a development committee that released it for public use in 1992. It’s an ISO standard: ISO 10918.

Although JPG and JPEG are the most common file name extensions, you sometimes also see JPE, JFIF and JIF (not to be confused with GIF, which is something else altogether).

JPEG works best with bitmaps of continuous tone, most commonly seen in photographs. It can work with 8-bit greyscale, 24-bit colour but not 16-bit greyscales and 48-bit colour. It supports several colour spaces: RGB, sRGB, CMYK, YCC (a TV format). It cannot contain “alpha” channels for spot colours, transparency or masks and it will not preserve multiple layers or embedded paths. ICC profiles for colour management can be attached,

Metadata such as date, copyright and photographer’s details can be embedded, including EXIF data from digital cameras or scanners.

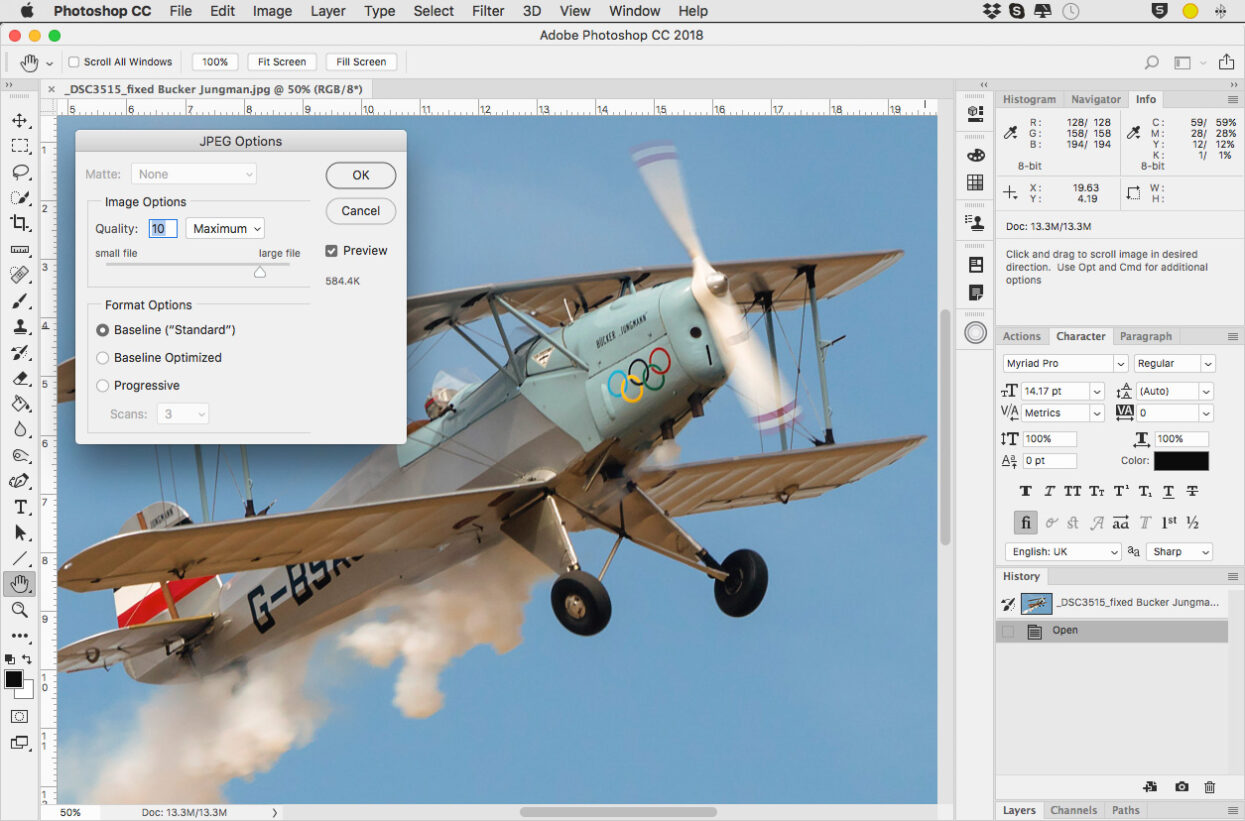

The most important attribute of JPEG is that it compresses image files down to much smaller files. It uses “lossy” compression which progressively loses image quality – the higher the compression the smaller the files, but the worse the image quality.

Applications that create JPEGs usually offer a choice of compression levels, which may be numeric from 1 to 12, with 12 giving the highest quality/largest files and 1 giving tiny files that are virtually unusable in print. As a general rule a setting of 10 (in Photoshop) or High quality (in InDesign, Acrobat etc) will give compressions of about 10:1 without a quality loss that shows up in print. Greater compression than that results in ever worse quality.

Note that once you’ve thrown away quality by using a high compression setting (say 3 to 5 in Photoshop), you’ll never get it back. Even if you open that file and resave it with a high quality setting, the damage will be done.

Quality loss in JPEGs shows up as “artefacts,” for instance halos around details such as lines and lettering, or blocky posterisation on areas of subtly changing tones, such as skies or faces.

Caption: Photoshop’s JPEG menu is typical in offering a choice of image quality, a preview of how this looks, and a choice of preview types for website display.

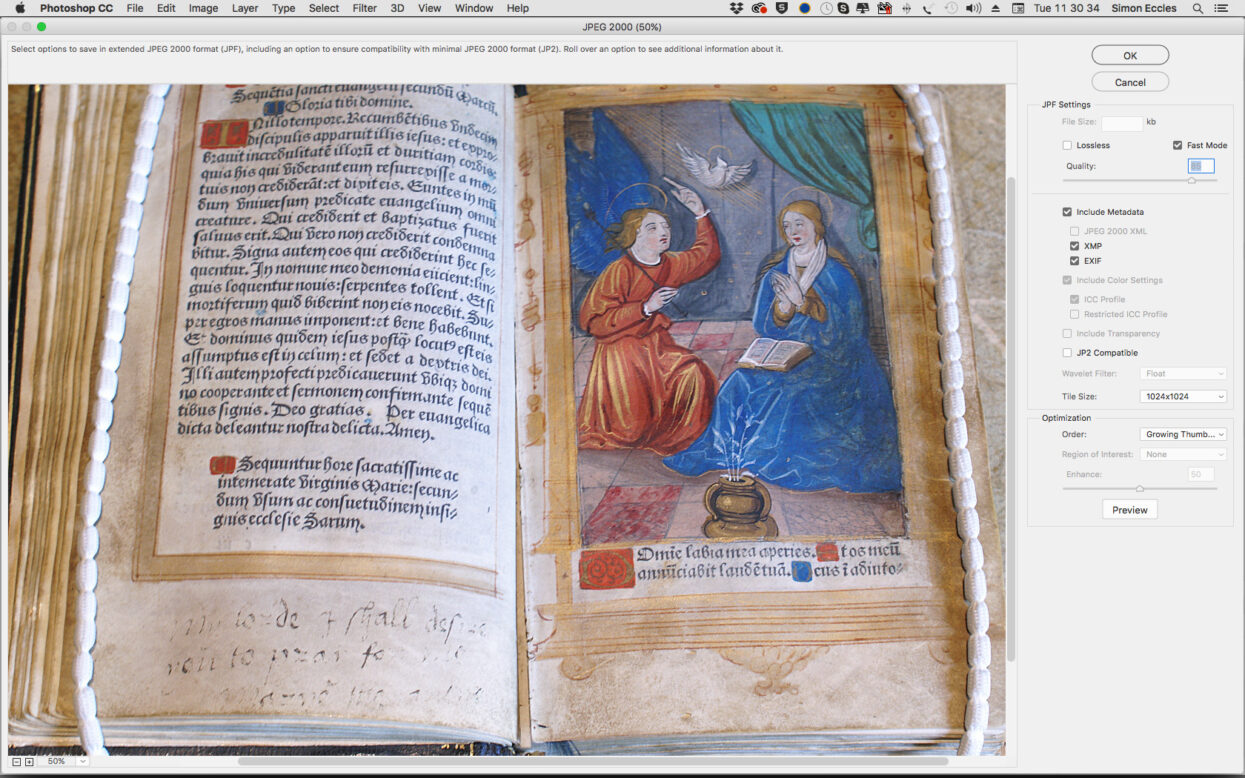

JPEG 2000 (.JP2 or .JPX)

JPEG 2000 was introduced in 2000. Improvements over the original include the elimination of blocking artefacts (though haloes remain), and support for 16-bit greyscale or 48-bit colour in any colour space. Transparency layers and alpha channel masks and spot colours can be preserved. There’s provision for lossless as well as lossy compression in the file writers. Although it’s still an export option in Photoshop, most people still use the original 1992 JPEG.

Caption: Photoshop’s JPEG 2000 menu offers additional options compared to the original JPEG menu.

Illustrator (.AI)

See Adobe Illustrator, part 1.

InDesign (.INDD, .IDML, .IDNT)

See Adobe InDesign, part 1.

Microsoft Publisher (.PUB)

The native format for Microsoft Publisher, a basic layout program distributed with some versions of MS Office. Some versions of CorelDraw will open .PUB files, but cannot edit, convert them. Note Aldus/Adobe PageMaker also used the .PUB extension, but these files are different and not compatible with Publisher.

OpenEXR (.EXR)

A file format developed in 1999 by Industrial Light & Magic for computer graphics in movies (CGI). It can store 32-bit high dynamic range bitmaps with additional channels for specular lighting effects. There’s a choice of three lossless compression methods. EXR is rarely seen in print applications but it can be opened and converted by Photoshop, Affinity Photo (which can also write .EXR) and some dedicated high dynamic range (such as AuroraHDR and Photomatix) and panorama processing apps (such as PTGui).

PCX (.PCX)

Stands for Picture Exchange. Originally the native file bitmap format for PC Paintbrush, an early graphics program for PCs running MS-DOS, it went on to be widely supported by other graphics apps. It’s still supported today by many Windows apps and all current versions of Photoshop can open and save it. It supports 24-bit RGB colour with an 8-bit transparency channel, and is losslessly compressed. The earliest versions only supported 8-bit RGB (256 colours) and so were similar to GIF.

Photoshop (.PSD)

See Adobe Photoshop, part 1.

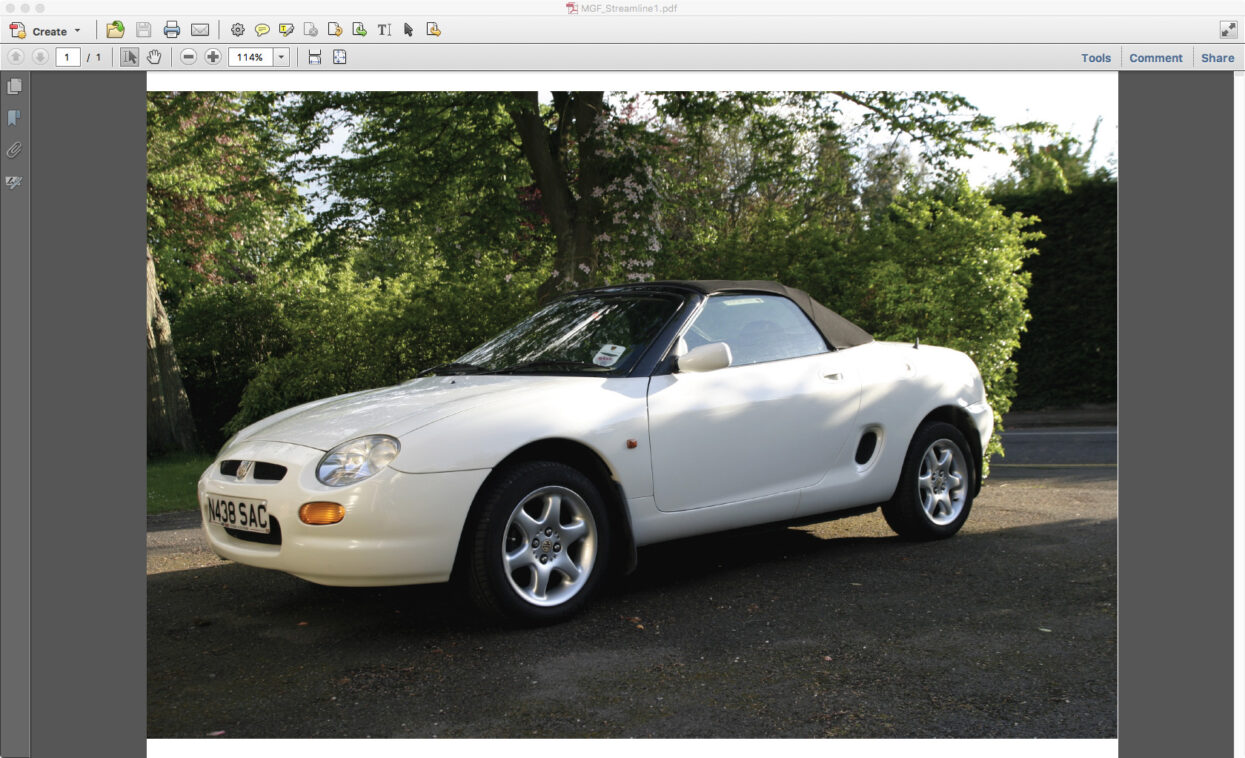

PICT (.PICT, .PIC, .PCT, .PCT1, .PCT2)

Early Apple Macintoshes had a native bitmap and vector graphics engine called QuickDraw. Programs that accessed QuickDraw could save files in the PICT format, which could be opened by any other QuickDraw-enabled program. Apple started to drop PICT after the introduction of OSX (now MacOS), which uses PDF instead.

Photoshop CC will still open some PICTs but not the very old ones. InDesign CC will place PICTs in documents, but the current QuarkXPress 2018 will not. The Preview application supplied by today’s MacOS will open any PICT but can only export them as PDF. However PDF editors such as Adobe Acrobat can then re-export these in a choice of image formats.

Caption: The car image is an old PICT file from about 1999 that has been converted to PDF by Apple Preview. It can be re-exported as a JPEG, TIFF or other format by Adobe Acrobat.

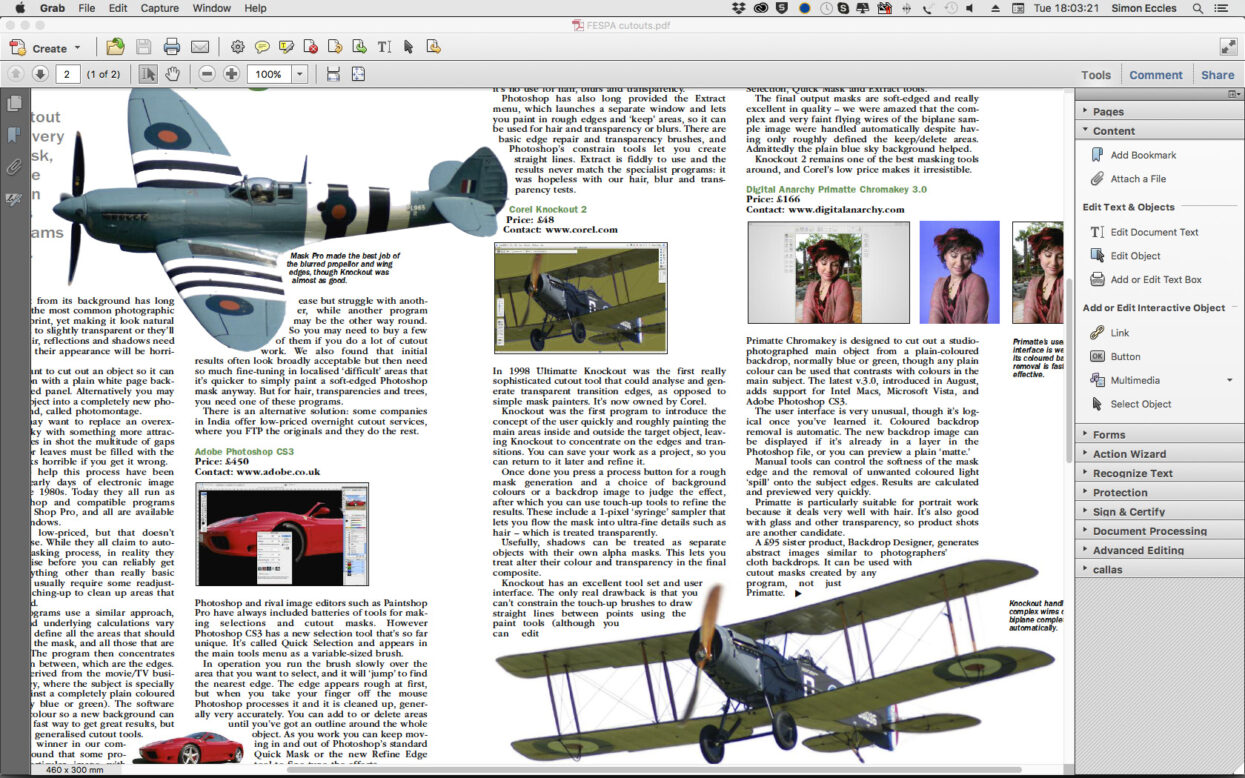

Portable Document Format (.PDF)

The most important file format in print. It’s a document exchange format that can contain virtually any text, graphics, layout, video and multimedia elements, plus colour management and production intent instructions for automated workflows. It is most professionals’ choice for sending and receiving job files because everything needed to print is included and nothing can get lost along the way.

Most professional layout and design programs can export PDFs with a choice of settings. So can word processors. Today’s Apple Macintoshes and Windows computers can convert and save any printable file to a PDF as part of their standard print menus.

Professional print digital front end software (often called RIPs) from all manufacturers can process and print PDFs efficiently.

Adobe developed PDF in the early 1990s and handed it over to the ISO to become an open standard in 2008. There have been several versions over the years, most of which can still be written by compliant programs – PDF 1.2 through to 1.7 are still all in use. PDF 2.0 has been announced but so far there are no commercially available applications that can write it.

There’s no space to list the differences, but for print purposes PDF 1.3 supports printable CMYK colours (as well as RGB), while the others up to 1.7 progressively added support for features such as layers and transparency.

PDF/VT was devised to support variable data digital printing, and PDF/A is a version for long-term archiving.

It’s important that the correct PDF settings are used for correct print output. PDF/X (see below) enforces some correct settings. Pre-flight programs are often used by professional printers to analyse PDFs on receipt so problems can be detected and sometimes automatically fixed. Examples of pre-flight programs include Adobe Acrobat Pro, callas pdfToolbox, Enfocus PitStop, Markzware FlightCheck or OneVision Asura/Solvero.

Caption: A PDF contains all the elements that make up a printable document, including layout, text, fonts, images and metadata, all in the same file.

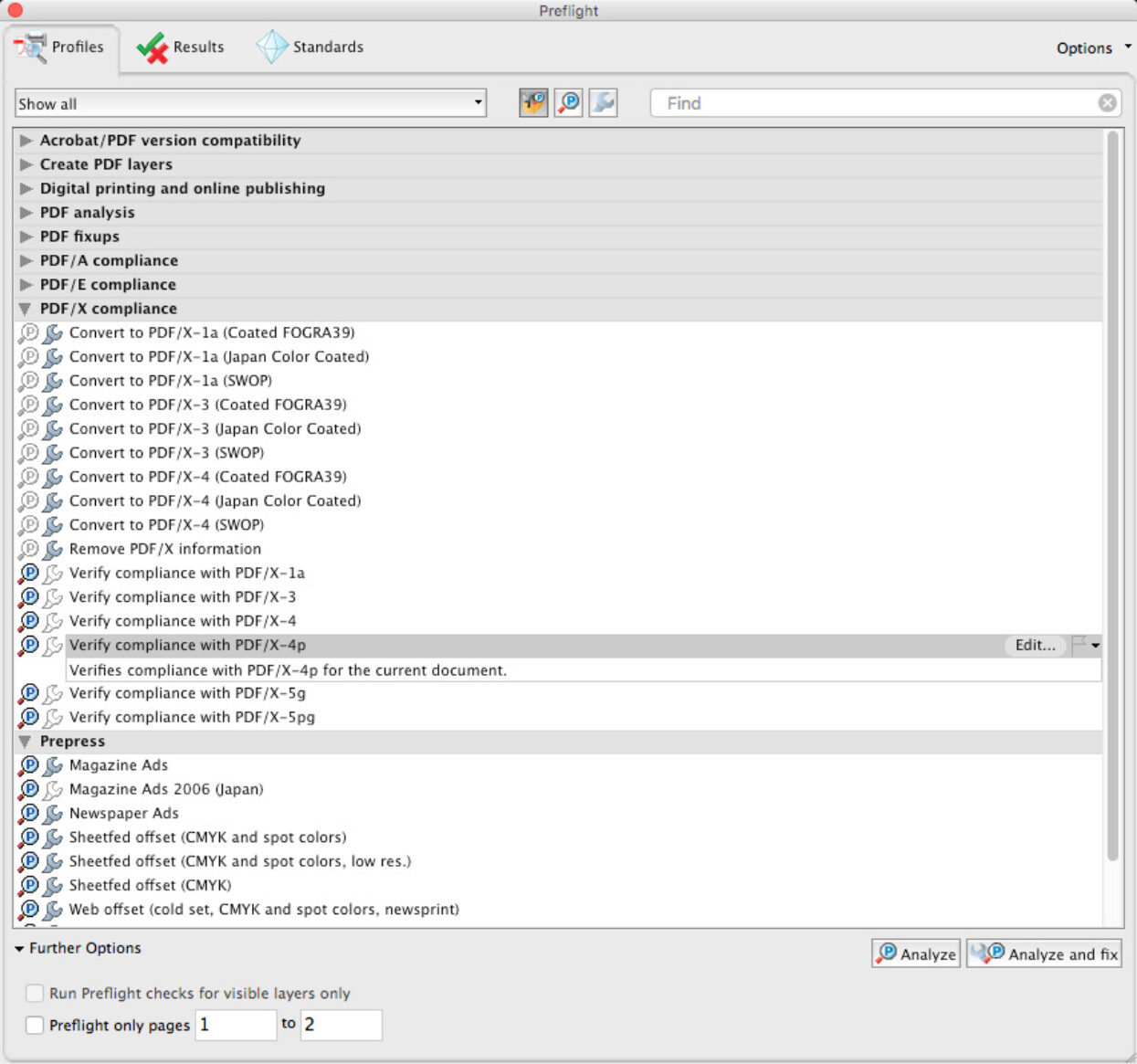

PDF/X (.PDF)

PDF/X is a series of variations of PDF files intended to ensure they print properly. A PDF/X file requires that certain settings are made, and other settings are no made. This allows “blind transfers,” where the receiver can be confident that a compliant file will print properly on their system. A program that writes a PDF/X will normally check and verify that the settings are compliant and will refuse to save it unless any problems it identifies are fixed.

As an example the original PDF/X-1a demanded that PDF 1.3 was used, only CMYK colours were used and that all font characters were embedded. Transparencies and layers are not supported by PDF 1.3, therefore neither does X-1a.

New versions of PDF/X have been introduced over the years, notably X-1, X-1a, X-3, X-4 and X-5. The later variants allow the use of layers, RGB, spot colours, colour management, layers, transparency and so. This is useful for some cases (such as wide-gamut six and eight-colour inkjets, and files with transparent text and shadows that may need to be edited at the last minute if, say, a price changes). An X-6 will be introduced in 2019 to accompany PDF 2.0.

Building further on PDF/X, the Ghent Workgroup, a voluntary industry body, develops specifications that define settings for particular applications, such as newspapers, magazine advertisements and packaging. These can be downloaded freely from the GWG website (www.gwg.org).

Programs that export PDF/X of various types include Adobe Illustrator, InDesign, CorelDraw, QuarkXPress and Serif Affinity Publisher. However, the file name extension remains .PDF so it’s hard for a receiver to tell what they’ve got unless they run it through a pre-flight program.

Please note that Part 1 covers AI to DNG and Part 3 covers PICT to XMP

Caption: Adobe Acrobat can convert PDFs to the various PDF/X types, fixing most problems and verifying them a compliant.